|

It is easy enough to come across those perfectly pinned posts online. With titles like Things All Great Teachers Do, Top Ten Habits of the Best Teachers & What All the Best Teachers Are Doing, it's easy to start comparing oneself to the sea of many. We often think about experience, tenure, types of districts served, and possibly test scores when thinking about if teachers are doing their jobs.

Lacking, however, are the posts written by children. The students. I am a firm believer in asking the kids. We spend time in the teacher lunchroom or meetings making decisions about children, often not including them in the conversation. So, I have decided to pull another chair up to the table. One to be occupied by our most important critics, our kids. I gave some of last year's students this prompt: what is it that makes a teacher good? What you find here is their responses. Published to this blog for all to see and savor. The first in this series is from a student I know I will never forget. His sharp wit and curious imagination is exactly what you would want in a student. He is wise beyond his years and in my humble opinion, has a writing career ahead of him if he really wanted it. He is the famed author of The Chicken President series that took our fourth grade classroom by storm last year. If you follow me on Twitter and Instagram, this is not the first you are hearing of this series. Here is Cameron's response to his teacher's summer writing prompt. What Makes a Good Teacher By: Cameron Basically it is caring. A teacher who doesn’t care won’t develop a good relationship with their students, causing a problem. A teacher who is willing to put in the time, effort, and commitment to his or her job is more likely to bond with students, creating a safe place for students to come in time of need. As a student, I really felt that my teachers were there to help me. I know they watched out for me because they pushed me to be my best. The good thing about having a teacher like that is that when you are struggling in the classroom, you always have somewhere to go for help. Though teachers should care, they shouldn’t always go “easy” on you. Perhaps the best thing that makes a good teacher is pushing you to be your best. Like my teachers say, “when you think you have finished, go back, because there is always something else you can add.’’ I love that they will always push me until my work is 100% perfect. Also, a teacher who will actually listen to their students will be better off. Lots of teachers are great, but some go above expectation. From personal experience, my teachers have been great, but to the ones that can meet this criteria, i’d give you an A+. Check back for more student responses, and feel free to leave your thoughts in the comment section. I know the kids would love to see them.

1 Comment

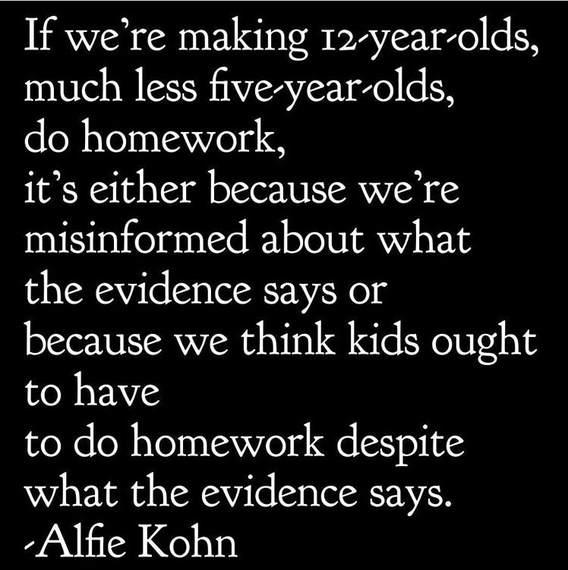

The never-ending debate trudges on. Should kids have homework? If so, at what ages and how much? In order to examine homework and it's implications, Valencia Clay and I have taken on some required reading on the topic. We have examined our own situations at teachers of fourth and eighth grade students, we have measured socio-economic factors and composed a conversation on the topic. Our collective goal is not necessarily for everyone to up and abandon homework, but rather to pull back and think about how it is used and whether it can ever be a catalyst for "leveling the playing field."

Fellow edu-blogger, Valencia Clay, teaches 8th grade and I teach 4th. The purpose of homework differs between elementary grades and middle grades, so we can came together to have a conversation about the issue. *** “Simply put, American parents no longer have the time to give their children the help they need with their homework.” SR: Our children spend on average seven hours a day, thirty-five hours a week in educational settings. Most full-time working adults average approximately forty hours a week. When I step back and think about these numbers and think about what has already been asked of my nine year olds during those thirty-five hours, providing them with an absence from homework seems to be the only humane option. With families working multiple shifts, childcare being vastly different in each home, and guardians working to spend just an hour or two, maybe just minutes with their children a day, it really does seem that time has run out. One might counter with an argument that the parents that do have time, do not spend that time supporting their children with their after hours work. My attitude is this, American parents and guardians (most of them) want what is best for their children. When we leave them no time during the week to make it happen, it is not unbelievable that weeknights with families end up being for talking, enjoying a meal together, shuffling kids to after school activities, or passing like ships in the night. As educators, we must understand that the makeup of our lives outside of school, do not always look the same as those of our families. VC: In the middle grades and beyond, that notion is unacceptable. However, as educators, we cannot allow the heavy freight of homework to fall on our students’ parents alone. An interloping line between parenting and teaching forms when we do not consider who they are as individuals and the amount of work they do to provide for their families. We have to be demiurgic and intentional when setting expectations that revolve around family engagement. Teachers can begin assigning family-based tasks that allow parents to be their authentic selves, let their child see them as intellects, and give them the chance to model critical thinking. Before any assignment is tasked, a parent-homework survey should be completed so that we, as teachers, will know what to expect from parents. It may include questions about their educational background, work hours, and whether they are in favor of family-based assignments. Make the questions as respectful as possible. Show a peer that is a parent before sending it home to make sure that it portrays your true intent: to build community in their home that engages around completing homework. “The demands we make of our children often reflect the worst as well as the best in ourselves.” SR: Alfie Kohn once said “In most cases, students should be asked to do only what teachers are willing to create themselves, as opposed to prefabricated worksheets or generic exercises photocopied from textbooks. Also, it rarely makes sense to give the same assignment to all students in a class because it’s unlikely to be beneficial for most of them.” When I first began my career as an educator, I gave generic homework because all of the teachers around me were doing the same. Guess how many of those teachers were creating their own homework? Almost none. Guess how many of them individualized what they sent home to actually meet each child’s needs at that given moment? None. I am in no way suggesting that this fits the mold for all educators, but we would all be kidding ourselves if we acted like the vast majority of teachers did offer homework in this fashion. What if students instead of spending time on traditional homework modeled more of the homework many of us do? The kind of homework with pure curiosity at the core. That kind of work where our engagement level is up because we feel empowered by the possibility of learning something new, something that means something to us. I am talking about the work where we have to know the answer to our question, because it is burning inside of us. How can we support this kind of inquiry with our kids? VC: This is so true. At my worst: I have gone weeks without a homework assignment. Then, when I tried to assign something for the students to do outside of school, no one got it done. It was a joke. That experience made me become the teacher who gives arbitrary homework every night, just to maintain consistency. I could not even keep up with grading those daily assignments and my students began to catch on, which meant they took the homework as a joke, again. Both of these instances could have driven me to end homework once and for all but I could not do such a thing because I knew my students needed and deserved exactly what Stacey described as, “homework with pure curiosity at the core.” At my best: We do not call homework homework, we call it life-work. When we are in the heat of a lesson, I may come up with an assignment on the fly, something that is directly related to the lesson of the day and was conceived out of a teachable moment. Generally, I may assign an ongoing, independent critical-thinking question on a Monday and allow students multiple days, over the course of their learning that week to complete it. This is where the term life-work comes in because the question is always one that makes them look at things from a new perspective… its life changing! I also make many of their assignments visual now, instead of forcing them to do writing assignments that I cannot keep up with or reading assignments that drain them after a long day. Visual assignments are much more fun and creative. For example, if we are learning about theme, I may have them bring in an item from home that metaphorically displays the theme of the short story we read. This, I find, is actually more challenging than just writing a 5-sentenced paragraph about the theme. For some kids, it becomes so hard that they need a couple of days to see the examples their peers bring in. No, not all teachers are assigning tasks like this but it is not because they cant or do not want to, it is because they have not learned how to do it yet. We should not end homework, we should put our energy into teaching teachers how to be innovative when assigning it. “Because schools cannot control the home environment, homework raises the profoundly difficult question of how to achieve a leveled playing field.” SR: If we want a leveled playing field in education, homework is not the arena. Homework will never, under any circumstances, ever, be a level playing field for our kids. While some children are listening to audiobooks in the back of their mother’s minivan on the way to soccer or music lessons, some are cooking their siblings’ dinner. Some of our children are homeless and do not have materials or a space to use to do their work. And while one might be swayed with heartfelt stories of resilience, shaming children or acting as though they are not doing enough in these latter situations would show a complete ignorance of the real lives so many of our kids are already leading. Punishing a child for not having their homework done, a child in a situation where survival is the number one priority, continues to be one of the most shameful practices of the US Educational System. VC: If homework is the only way to achieve a “leveled playing field”, we should all consider ourselves doomed. Homework is by definition, a reinforcement of the learning or a pre-assessment of what will be taught – never should it be considered the lesson. The classroom is where we prepare our students to live in their limitless potential, despite the degree or nature of the home environment. In places where we know a student does not have parents at home or a home at all, we can use that as a reason to pair them with a mentor in the community. Chances are, they will appreciate the mentor and maintain a love for learning at the same time. Homework does not have to remind us of the differences between our students but when it does, we should never ignore them, we should embrace them. “How can we raise “whole children” when they have little time to do anything other than school work?” SR: I find it hard to believe that so many educators expect my nine year olds to hold not one, but two full time jobs. A child attends school weekly, averaging almost the equivalent of a full-time job an adult might hold and then is expected to put in overtime when he arrives at home. The moments that should be spent taking a deep breath, running, playing, talking, exercising, relaxing, just being begin to not exist for children. I often hear teachers complain about children lacking problem-solving skills. It is in these moments that I wonder if these teachers realize they are the ones robbing our children of the very experiences that build problem-solvers. Experiences like play, and knowing that if our children do not have the opportunities to feel safe, loved and carefree at home, then we better be pulling out all the stops so they can have these chances at school. Life lessons are learned at the hands of those in our families. Storytelling is valued and honored in many different cultures and across religions. Are the overtime requirements placed on children providing them opportunities to connect with their families and learn their stories? VC: Unfortunately, this research has proven to lack the timelessness that I expected when I initially purchased the book. It was developed way before the Internet was a common household tool, before social media, and before the marking of the neo-civil rights movement that we are living in today. In urban areas, like the ones I have taught in, many students do not participate in more than 1 extra-curricular activity. The lack of funding for youth programs leaves our children with more idle time to find who-knows-what online, while intentionally crafted homework assignments prompt freethinking time. Who says a reading teacher cant assign a musically-grounded homework assignment? Who says a math teacher can’t do the same? Is it a crime for the science teacher to ask to students to go the museum on the days that it is free to do independent and fun research of their choice? If homework is assigned intentionally, we can use it to shape and mold our children into this “whole” child we want. However, I believe building the whole child has less to do with homework and more to with teaching our students to identify their triggers and adopt tools for social-emotional adversities such as anxiety, doubt, and depression. This, again, is about more than homework – its life work. “It’s simply the fatigue factor that keeps these programs from having the desired outcome.” SR: Alfie Kohn spent much time with the research around homework as he prepared for his book The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing. To quote him again “For starters, there is absolutely no evidence of any academic benefit from assigning homework in elementary or middle school. For younger students, in fact, there isn’t even a correlation between whether children do homework (or how much they do) and any meaningful measure of achievement. At the high school level, the correlation is weak and tends to disappear when more sophisticated statistical measures are applied. Meanwhile, no study has ever substantiated the belief that homework builds character or teaches good study habits.” Can it be the fatigue factor when the research so blatantly states otherwise? Are we blaming parents and guardians for something we already know to be ineffective? VC: I have taught in a school that begins at 7:30AM and ends at 4:30PM. These hours make the requirement of homework sound like pure torture. Students do not need adult level responsibilities but it is our responsibility to build on their creative stamina, even after the school day ends. The research may not prove homework to be effective but should we allow social media to take the place of practicing newly acquired skills? Do we really want to engender a generation of followers and consumers instead of leaders and creators? I understand the need to create or finish a product can become daunting and lead to perfectionism and depression but the reality is, the power to create is not easy to harness, assigning at least 1-2 independent, research-based, or artful assignments a week will be a catalyst for the determination and drive that our students will use outside of the educational setting. “Maybe its time parents finally admit… homework disrupts family life beyond a tolerable limit.” SR: I will admit, as a parent, that homework does disrupt family life. My oldest daughter will be a third grader in approximately two weeks. She is a child who loves to learn, but does not love school. I saw it in her with the “optional” packets sent home in kindergarten. She had no interest in spending her time outside of school working on worksheets. Who could blame her? When first grade rolled around, it got even worse. Homework that year was required and my bright, articulate, rule following child would scream, kick and cry her way through her work. Work, by the way, that required little to no thought on her end. What was the point? It was certainly hard to see it as a parent and educator watching the social experiment unfolding before my very eyes. I was watching a genuine love of learning being pulled from my child. She could have been playing, interacting with her family in positive ways or problem solving as she lived her life. Instead, she spent many nights fighting with me over something I understood had no value. Disruption, unlocked. VC: This can only be said if a school is not collaborating on the assignments. Homework should be given in collaboration with other teachers, parents, and the voice and choice of the students. Yes, 4 hours of homework a night is unacceptable. This is why each subject should claim their homework night and move forward as a school in fidelity to such agreement. Administrators and teachers of the arts should be assigned the task of working with subject areas or grade-levels to alleviate “homework packets.” If the assignment is not meaningful, it should not exist. “As Americans, we don’t like to talk about class, but when we talk about the homework spread across the kitchen table, we have to recognize that some tables are bigger than others. Our class position in this society influences our ability to help children with their homework in subtle and complex ways.” SR: Class affects us all, like the quote says, in subtle and complex ways. It provides us all with opportunities or maybe it doesn’t. It baffles me just how many educators lack the skills of picking up on these subtleties. Maybe you send home a homework assignment where children are to write about their favorite thing they did over summer break. If you are not being mindful about families and their experiences, you might be thinking this is an assignment anyone can be successful with. It took a child telling me that his favorite part of summer was when he got to walk to the Carryout with his dad. I had other kids talking about trips to Disney World and this child is talking about a visit to the local gas station. Other things like expecting all parents to have access to smartphones, the Internet and printing capabilities, again, just show our own ignorance and lack of understanding about our families. Not all guardians work 9-5 jobs or have their own means of transportation, yet teachers are rolling their eyes at the empty chairs during parent-teacher conferences. Until we step back and do the work when it comes to getting to know our families, homework becomes yet another startling reminder that we aren’t trying hard enough. Do parents have access to support so they can assist their kids? And do our assumptions about what parents “should already know” get in the way of building partnerships? Are you available to help coach or even speak with them at a time that works for their schedule? VC: Its equality versus equity. Differentiation is key here. If we recognize that there are nuanced representations of class in our students, then we must develop a homework schedule and assignment bank that all students can access. In the case of homework, every student should be tasked with what they need as individual learners. If we are rallying to end homework because we do not want to go the extra mile of differentiating it for our learners and developing a burgeoning rapport with their parents, we should not be teachers. “Rather than connecting us in a meaningful way with the school, it often alienates us from our children as they are forced to take on their role as student while we don the teacher cap.” SR: We know that a child’s first teacher is their parent. The ways our families teach us are organic. They submerge us in language and touch, little nuances that are special to each family unit. This is the kind of genuine teaching that should be expected of parents and families. When we replace storytelling, survival techniques, religion and customs with basic comprehension and direction following, we pull at the strings of the parent-child relationship. We put strain on the unit by forcing children to participate in mundane tasks with their parents at the front of the ship. Mindlessly tasking and dragging them along, kicking and screaming out of sheer boredom. If we want our children to have strong family units, we should find ways to help support their connections with one another, not add unnecessary strain. VC: My grandmother, who raised me, dropped out of school in the 8th grade. She never read to us, helped or checked our homework unless it was an assignment that required her to do such. I remember reading Shakespeare in 9th grade English. We were told to analyze the quote, “What’s in a name…” and to find the meaning and history of our names. Only she knew the history of the Clays and why my mother chose Valencia as my first name. I also remember having to write a list to make a recipe for chocolate cake in my math class, and yet again, only she had that! Together, we were both students when completing these assignments. She was learning about Shakespeare while I was learning about myself. These are just a few examples of authentic homework assignments that can be done in a home of parents who may or may not be educated to the highest standard. It is okay for parents to feel like students at times. This does not mean that we are donning the teacher hat, this means we are promoting learning as a life-long process. “Homework must be examined in the context of how it affects the organization of the family and the family structure as well as how its impact is felt across socioeconomic lines.” SR: Bottom line, we know the research and it supports not giving students homework. We also, as smart educators, examine a lack of equity when it comes to the playing field of home education. Taking all of these things into account: the strains on the family unit, impact across socioeconomic lines, lack of effectiveness supported by years of research… what’s the point? At what juncture do we decide that the quickest move we can make in the work of leveling the playing field of education is to actually pull homework from the table? VC: I totally agree. Homework must be examined but not ended. My journey with workshop has been a long one, and one that I continue to pursue. A few years ago, when I suddenly became very interested in learning to be a better teacher, I started reading more professional books (on my own), blogs and online articles. I started listening to teacher experts and what they said about how they spent their reading and writing time.

I started to notice a trend, that almost all of these top literacy people, people whom I knew I could trust, were all using Workshop. This made me think that if they all felt like it was the best way to present reading and writing to their kids, who was I to do or say otherwise? I jumped right in and decided to try it out for myself. I get personal messages DAILY asking me for more information about Workshop. In this post I will lay out some resources for teachers looking to learn more about the Workshop format and the logistics of implementation. This is by no means an end all be all, just a list of things that have helped me along the way. Reading Workshop

Writing Workshop

I hope this post helps you get started with Workshop. My learning has come a long way over the past few years, but I can honestly say that I don't need a "program" to teach reading and writing. Now that I know about the layout of Workshop and I have some key ideas under my belt, I feel more comfortable with switching things up and trying new things. A lot of my learning this summer has been surrounded by inquiry, and my next goal is to continue to get a handle on reading and writing workshop, while including more inquiry and space for student wonderings in the units. The two complement each other and I am excited to see how they come together. Disclaimer: I do not level my classroom library, my kids do not know their reading levels, my kids do not use the homework or reading logs in the unit of study. This is where my Nancie Atwell, Donalyn Miller and Donald Graves training comes into play. Even though some of these resources suggest those things, I will never do them. I believe it is a basic right for my kids to have full choice when it comes to reading and writing. I also believe that for me to help them become better readers, writers and thinkers that I cannot be the one placing labels on books that tell them where they go. I work to help them develop the strategies they need to find books and find writing inspiration outside of the walls of our classroom. Bottom line: This way of teaching does not require "stuff." It requires a shift in thinking, and the willingness to provide many books, a lot of time to practice and a skilled coach who leans into kids as they work. If you have any questions or recommendations, please share below! This was originally shared as a short Nerd Talk at nErDcampmi 2017. The audio will be made available this fall on the Nerdy Book Club Podcast. I cried quite a bit, so I don't know how audible the audio will actually be. It is my hope that you find some comfort, heart, or confirmation in my words. If my words upset you and you feel offended, that's okay too. You are the one that needs to hear it the most. This is a portrait of one child's piecing together some of her childhood memories surrounding school. I do not have a learning disability, I do not live in poverty. But at times during my schooling, I was made to feel as though I wasn't enough. At times, I was made fun of for my thrift store clothes. Looking back, I never felt like I wasn't fully provided for, because I was, above and beyond. My parents were young and they were and still are smart, and caring. They are still married, they put me through college and they continue to teach me the value of hard work and not buying things I don't have the money for. This is the power of a caring relationship (my family and parents) versus the relationships I was often met with at school. So tread lightly, educators. Your words, your looks, your assumptions will have lasting impacts. In my case, there were many positive experiences with outstanding teachers, but they don't erase the bad ones.

I stand before you today, a reader, a learner and a thinker, despite some of the educators I have had along the way. I can count on one hand the positive memories I have associated with reading as a child, that were connected to my educators. A Kindergarten Intervention Specialist whose room I would reenact There's An Alligator Under My Bed, complete with paper bags filled with plastic fruits and vegetables. My third grade teacher's Superfudge voice is still stuck in my head. An ordinary pebble given to me by my librarian after a read aloud of Sylvester's Magic Pebble. The kind of pebble that made me, as a child, feel like anything was possible. And perhaps the most lasting memory, was meeting THE RL Stine, an Ohio author you may have heard of before, in my elementary school library. Sidenote: our current librarian was weeding the collect at my elementary, I work in the district where I went to school. She found a copy of The Haunted Mask signed to "Central Elementary Friends" and she gifted me that book this year. My time up here could be filled with the negative reading experiences over the course of my education. Being one of a minimal amount of seventh graders to fail the reading proficiency test. I spent the summer in summer school being drilled and killed. Finally giving my middle school reading teacher the most genuine smile her face showed me in those two years. Which, may seem endearing, but in actuality it was damaging. It made me feel like all of my worth was wrapped up in her being able to check me off a list of students who had passed. Or the time in a high school social studies class where I spent my time socializing because I didn't understand the content, and maybe because I was bored, only to be called sorry by my teacher, in front of my peers. I am not an advocate of children being disrespectful, but sorry? Sorry that you can't engage the youth. Sorry that you hate coming to "work" every day and you make sure we know it. Sorry that you feel giving your kids worksheet after worksheet is actually teaching. Sorry that you only saw a problem, when I, a child, stood before you. A child with two young parents. A child with WIC on her doorstep and thrift store clothes on her back. A child who struggled a little bit with reading, but loved books more than anything in the world. My teachers had good intentions. I'm sure. But I am here to tell you that the world does not need your good intentions. I do not need them, and if I do not need them, your kids definitely do not need them. We don't need what makes education easiest for YOU, the adult in the room. We don't need a clip chart on the wall showcasing all of our mistakes. Your cute clip art doesn't make it easier to be dehumanized in front of our friends. We don't need novel study packets. We don't all need to read the same book, at the same time. We don't need to know our reading levels, because none of you in this room know yours. We don't need the assumption that an empty chair during parent-teacher conferences means that our families don't care about our educations. We don't need to spend all quarter reading ONLY ONE BOOK. We don't need a carpet spot because you don't understand that our young bodies were built to move. We don't need every single book in our classroom libraries to be filled with kids that don't look or feel like who we are or the families we are a part of. We don't need you telling us what to think. What is fair and just. And we don't need you to tell us to be silent when all we want to do is scream. The world does not need your good intentions. In Rita Williams-Garcia's newest book, Clayton Byrd Goes Underground there is a quote I have to share: "Around Cool Papa, Clayton didn't feel like a kid. He felt like a person." This is what we need. Books, at our fingertips. In every room of our school. Books about the things we care about, not the things you care about. And teachers who love talking about those books with us. Smiles. The kind that let us know that there is no other place you would rather be, than here, with us. Laugh with us, let us see that young person with the fire in their belly who decided they cared so much about the world that they wanted to help raise its children. Supplies. So we don't have to be embarrassed over Rose Art, not Crayola. So we don't have to see that disappointed look on your face when we happen to lose our pencil, again. Relationships. Get to know us, get to know our families. Care about us and listen to us when we speak to you or when we ask you questions. Be calm when we are overcome with big emotions. Know us enough to know that some of us get our siblings up and ready for school each day. Choice. Let us choose whenever possible. Books, pieces of writing, seats, read alouds, classroom set up, curriculum. How can we be expected to make real decisions when no one is allowing our voices to be heard? Humility. Instead of being annoyed that I am an hour late, let joy wash over your face when mine finally comes through that door. Instead of being agitated that I need to use the bathroom again, just let me go, as you would hope someone would let you go. And last but not least, truth and knowledge. Hard conversations, educators who know their growth and depth of knowledge has no fixed endpoint, books that tackle the topics we live with everyday. A platform for our voices to be heard, honest depictions of our world, multi faceted narratives, the ability to evaluate sources, a chance to critically examine our own biases and then the means to do something about them. I want you to stand up if someone in this room has ever inspired you. Inspired you to be a better person, inspired you to think harder and given you support when it comes to supporting kids. Look around, you are what we need. Teachers, authors, librarians, administrators... like Cool Papa who are dedicated to seeing us as people, not just kids. A fourth grade student sketches a plant during a Cincinnati Urban Gardening Field Trip, 2017

What does it mean to innovate? Innovation encompasses all that we do in life. It’s less about the term innovation and more about the mindset that should be the steady foundation, resting underneath. One must be willing to grow by getting uncomfortable and questioning not only the world, but the roles we fulfill within that space. As educators, we need to move away from technology as a mark on a checklist. We should move into a space where technology is merely a tool to help our creations develop. Technology can provide the software, so to speak, and the platform for sharing. We are in the driver’s seat when it comes to what we will create. Knowing that the best reading teachers are readers, and the best writing teachers are writers, shouldn’t all of our teachers be innovators? If we want children to embrace and take seriously the role of innovator, then we must be willing to be the guide on the side offering support and mentorship. This mindset encompasses all content areas and grade levels. It is for everyone, PreK-12. In my heart, the things I know to be nonnegotiable are students reading what they want and writing what they want. My whole classroom revolves around this belief that my kids deserve protected reading and writing time each and every day. Within this time, I value inquiry work and students exploring the things that matter to them. One book, one pen. These are the tools that will help us change the world, and these are the tools that I provide my students no matter the cost. All other things just do not matter if my kids do not have a voice and choice in all aspects of their day. Technology is the vehicle. Our ability to shed our comfort and move into spaces that feel difficult and necessary for growth, shows a lot about who we are as educators. Sure, we can be flexible when it comes to pop up assemblies and schedule changes, but are we ready to really disrupt our thinking on the assembly line education most American children are receiving? It begins with putting our kids first. Deciding that the right thing to do is to involve children in their educations. They should be making decisions about technology and every aspect of their educational careers. What we do for kids, we do to kids. Their educations should not be something done to them. Our focus should be kids and relationships with them first. Technology and reading the world can help us elevate their voices and give them the platform to share those voices with the world. But, it starts with us. The following is a reflection I completed for my second graduate class. This is only the last portion, but I wanted to have it in this space because I believe that others could benefit from these ideas/ revelations for a fresh school year start.

Guide on the Side This class has been a great blip on my teaching journey. I have learned alongside dedicated educators. Educators who have challenged my thinking with their smart ideas. Educators who think differently and provide a simplicity and perspective that I often struggle to find. This has all led me to the work that I am most excited about for the new school year. Three aspects that will be completely different than the ways I have started the year in the past: Inquiry Based Student Guided Curriculum Comprehension and Collaboration and Curious Classrooms will be the last two professional texts I finish this summer. These two texts provide inquiry units and lessons to help guide a switch to a student centered curriculum. I have to fight off the temptation to add any other texts into the mix. I also need to understand that C&C is mostly a guided resource that can be made into whatever I want it to be. This is my first step to planning for a fresh school year. Summer Setup I shared that I plan on having my incoming students come to school and help me setup our new learning space. This is the work that I am looking forward to. Getting to know these kids before school starts. Getting to see what they like and what types of environments help them learn. Getting to interact with parents and guardians before the year has even started. After our work together, I want the kids to be able to reflect on the practice. I want the opportunity to share what we do because I know it will be a powerful exercise. I plan on blogging, tweeting and Instagramming the experience, but I will have students choose how they want to reflect on the work. Opening this up for reflection will also tell me a lot about the kids and how they prefer to publish, jot ideas and develop their little pebbles of inspiration. Classroom Pet Inquiry This past week, I have had many questions about classroom pets. Naturally, I took to my followers on Instagram. So many teachers at my fingertips! Within minutes, seconds really, I had access to real-life classroom pet experiences and advice from those who had actual experience with the process. These teachers reaffirmed what I knew should be at the heart of this inquiry, and that is my students. Many encouraged me to get the kids involved with the decision and financial aspect not just because of fears and allergies, but also because of community building. My own inquiry (using Instagram as a tool) helped me find the hashtag #classroompets. Here were tons of visual representations, snippets and little bits of advice to guide my inquiry. Next, I found out about a classroom grant program that will help us finance our new friend. Within 24 hours, I talked with my teaching partner about a beginning of year inquiry pulling in math, science, social studies and of course, reading and writing. My own curiosity and idea drove my inquiry. I was engaged in my learning because I had access to innovative outlets and I cared about the topic. As I’m writing this now I am realizing that this could be the basis for every single exploration we take on this year. We can have an idea. A question. A wonder. We can have access and the ability to explore, if our schools let us. Link to my full portfolio, if you're interested. I just returned from my first professional speaking experience. I was asked to present at two of the 2017 Scholastic Reading Summit locations, which was both exciting and nerve-wracking.

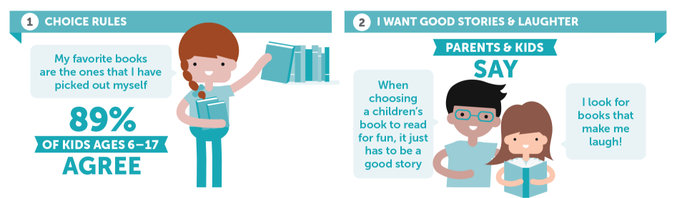

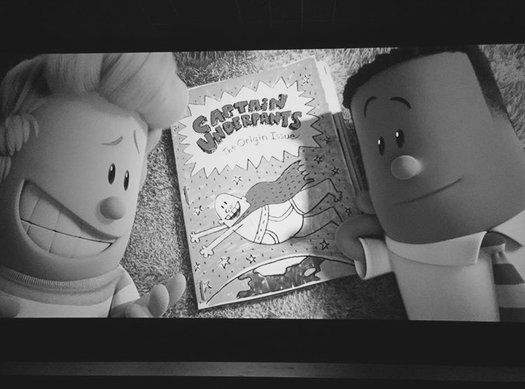

Did I have anything to say? Scratch that. Did I have anything NEW to say? I feel that I am kind of out here saying the things that many of us already know. Many of the things that so many teachers already do in their classrooms. Then, I realized that I am saying these things and sharing my classroom experiences mostly with educators already inside the kid lit community. Each time I step outside of that community, I worry about what I see. I worry about the posts flooding Facebook Literacy communities. I worry about the posts I see on Instagram. I especially worry about the general education questions that flood my DMs. A friend recently told me that you can tell a lot about where a teacher is in their journey by the questions they ask you. As someone who has come a long way since their first year of teaching, and as someone who still has many miles to go, I have recently been thinking a lot about how I approach these educators. I remember a few summers ago when I was filled with questions, more so than normal. It was the school year that a representative from the county told me that "I ask a lot of questions," in front of my colleagues during a PD session. It was also the year that I joined Twitter and stumbled upon the hashtag #nerdcampmi. I had just read Reading in the Wild, and could not ask enough questions. I wrote down every literacy person mentioned in the book, joined social media outlets with my educator hat on and fell down so many hashtag rabbit holes. It was a year of tremendous growth for me. It was a year in which I had a lot of questions. A lot of questions that probably felt stupid, or obvious to those I was asking. Now my thinking is hanging in the balance. Each day, the pendulum swings from "hey, let me get you some great resources for that" and "I'm still growing my learning on that topic as well," to "You just read The Book Whisperer and you STILL don't get it?!" It is an overwhelming piece and it is one that I think about more than I need to. I want to help others, like those that have helped me along the way. We need support from each other. I will help others. I will continue to open up dialogues (especially ones that teachers don't want to talk about), I will continue to post articles and link to research we all should know, as I hope others will continue to do for me, and I will continue to answer the questions I am asked, but at some point... I need teachers to start helping themselves. Yes, the community is out there to provide support, but I have put in a tremendous amount of self-guided work along the way. I have read many books, I have used trial and error in the classroom, reached out to others, and I've even taken to Google when I have a question that could easily... be answered... by a Google search. My frustrations are not with the questions asked. My frustrations lie in this space: when we know better, why are we not doing better? Kylene Beers said it best: If children want to learn vocabulary, they should read. If they need to develop fluency, they should read. If they need to learn about a topic, they should read. If they need to be a person they are not, they should read. If they need to grow, to stretch, to dream, to laugh, to cry, to find a friend, to vanquish a foe, they should read. We know this, right? Yet, what do so many teachers have children doing? Not reading. Timing reading. Counting pages. Counting minutes. Logging reading. Logging pages. Logging minutes. Leveling reading. Leveling kids. Leveling groups. Leveling books. Printing worksheets. Collecting worksheets. Grading worksheets. It just all feels like complete madness to me.  We should get something out of the way here. It is bogging down teachers and inadvertently, kids, everywhere. It doesn't matter that YOU don't like the book. I'm looking at you, parent or teacher, who is clutching your pearls at this very moment because I started with an image from the new Captain Underpants movie. Relax. Authors know what I'm talking about. You receive it in scathing Amazon reviews, you might receive a nasty letter from a parent who has never sneezed or burped or farted (say that last part in a Gru voice), or you might even be lucky enough to write a book that has been placed on a Banned Books list. As late as 2012, Alvin Schwartz's Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark was still making the yearly top ten list because of uptight people contacting the Office for Intellectual Freedom. This book was released in 1989 and if my elementary librarian had a record of the amount of times I checked it out, I'm pretty sure my mom would have said "wow, my kid was reading... and reading a lot. Well done fine librarians and Alvin Schwartz!" I was obsessed with all things scary as a kid. My attitudes about reading might be different now if I was censored when it came to checking out children's' books in my own school library. Look, no one needs you to publicly declare that you don't like Captain Underpants, or Diary of a Wimpy Kid. Guess who does? Kids. (And a lot of cool adults, like me). Need data to support that statement? There are now more than 164 million copies of Diary of a Wimpy Kid in print. When Old School was released in 2015? Over a million copies sold in the first week. (Independent, 2015). This is about them, not you. The last time I checked no master villains have been developed because of reading funny books. We probably could have defeated some epic jerk faces IF they had read funny comics as a kid. Scholastic's Kids and Family Reading Report shows us what we already know: kids love to pick out their own books. Just like adults do. It also shows us that kids want books that make them laugh. They want fun reading experiences. Books like the ones I've mentioned give kids exactly that. This article from 2012 sums up my sarcastic attitude towards these parents who are upset that their kids are having enjoyable reading experiences. It is all about Captain Underpants being the most challenged book of 2012. I highly encourage you to read it. This past weekend, my family went to go see Captain Underpants: The First Epic Movie. I haven't heard my husband laugh that hard at a movie in years. I was in tears because I was laughing so hard. My almost eight year old, glued to the screen. My three year old? Cried because we had to take her to the bathroom right when Professor Poopypants was getting his. Underneath the humor was this sad realization that Dav must have had years and years ago. So many schools are sucking the fun and life out of kids. Complaining that kids can't think critically when they haven't been given the time they need to play and explore their own interests. This system is bringing kids down and this movie highlights this, just like all of Dav's books. I believe if we as teachers, and parents, helped our kids find what they really love and gave them time to explore it, lives would change. My dad always gives me great perspective in this area. He has always been an avid reader. I am talking taking the whole family to Barnes and Noble to read and explore, whole room dedicated to his beloved motorcycle magazines, always something in his hands avid reader. I was explaining the movie to him and the commentary it provided on education. He said that his first favorite motorcycle magazine, Cycle, is what taught him writing mechanics. Not his teachers drilling isolated grammar and sentence structure, but reading an actual mentor text is what showed him how to write. He battled the stigma around being a kid that wanted to make and work on things with his hands. He became a reader despite the adults around him, limiting him. I want my kids to become readers with my help, not in spite of me. But how many of our kids are forced into these same situations because of teacher attitudes? This movie is powerful, just like Dav's books. The movie that I had posters for up in my classroom, and one that my fourth graders were pumped to add to their must see lists for the summer. Imagine if I would have had a bad attitude about that book and movie as their role model? I might not have had kids writing Dog Man inspired comics literally all year, I might not have had kids experience a resurge in the original series, I might have even decided to keep these books out of my library all together. In that case, what message would I be sending my kids? That I don't value these books and reading experiences. What an awful message to send to children. I won't be the one to do it. All reading experiences should be valued. LET KIDS READ! I am about sick of all these adults standing in the way! You want readers, so stop attaching rewards, AR quizzes, leveled baskets and shitty attitudes about children's literature. LET KIDS READ! The kids will find the comics. And then they'll read them. Stop being a baby. Sit down next to them and read them too. It might just lower that high blood pressure. My hardest work of the day is when my kids have settled in with their books. The lights are down low, but not too low. The windows are open to let in the breeze. It takes us a few moments to get into the zone. Once the crinkling of headphones bags, the logging-in on Audible, and the shifting of chairs comes to a halt, I get to work.

Conferences look different based on what readers need at the time. Some days I kid watch from a couple of different spots in the room and fill out an engagement inventory. On other days, you will see four or five kids huddled around my kidney table reading quietly as I check in with each reader. Most of the time, I will be working one on one with my readers. The goal is simple: readers spend workshop time reading, and I spend workshop time helping them with their reading. It is my job to help readers grow. To make them feel like reader is a name they are worthy of. They are worthy of the name, and sometimes it takes many conversations throughout the year to help them try that on that name, to help them own it. How can so many teachers continue to ask me how I know that my kids are reading? How can so many teachers continue to require logged reading, when the answer is as simple as the goal? Give kids time to read, access to books and then work to help them as they grow and try on the name of reader. Be there for the conversations, because I promise they are the best part. The conversations are taken to a new level when you are living a readerly life, yourself. Talking with kids about reading is the heart of workshop. Yes, I will work with readers on goals to help them grow. Maybe they are working to recognize pieces of plot in fiction to deepen their understanding. Maybe they are working on visualizing a mental movie as they read. Those things are all an important part of my work, but my favorite thing about these conversations is the heart that each individual reader brings to them. Last week, I met with a fourth grader who was rereading Kazu Kibuishi's Amulet series. First off, how advanced is that decision to reread a series? I started the conference by telling this reader that I was beyond impressed with this move. Then I asked him why? I like to keep things open-ended because let's face it, whoever is doing most of the talking, is doing most of the working. His response helped reaffirm why these conversations are so important. He said "The first time I read this series, I read with my heart. This time, I'm going to let my brain do the work." Profound. A fourth grade reader actually said this to me. Please tell me, where would he have added this response on a standardized test? On a reading log? On a multiple choice quiz? In a fat packet with literal comprehension questions for each book? There is no place for heart work on these measures. The place for heart work is during conferences. Conversations between two readers will tell you everything you need to know about a reader, and more. That day, I also met with about four other readers in his class. Keeping my check-ins at about five a day gives me the chance to meet with my kids once a week, at least. As I sat down next to another reader, I noticed he had a copy of Anne Ursu's Breadcrumbs, a book I had book talked just a few days prior. A book that I did not imagine seeing in the hands of this reader. I picked up Breadcrumbs and said "whoa, nice." He then said "Yeah, I am already 80 pages in and I really like it so far." I followed up with "80 pages? That's past the point of no return, what made you choose this one?" He told me that when he heard me book talk Breadcrumbs, it reminded him of Elsa from Frozen. He said he knew he wanted to give it a try because he liked Elsa and he hadn't spent any time reading fairy tales during the school year (that week we had completed a mini lesson on gaps in our reading lives). Then he looked over at me and said "This is my first big book." Being the outstanding actress that I am (I really wanted to cry), I simply said "wow, how does that feel?" He fidgeted with the book in his fourth grade hands and said "It feels really good." This. This is what I am talking about. That reader had no limits from his teacher. That reader was not afraid to tell his teacher that he likes Elsa from Frozen. He was not afraid to try something new, step out of the box because of the safe community in our classroom. The community is a pivotal piece, because if you don't have it, conversations might not sound like this. Conversations connect readers. Connected readers make up a community. Communities of readers can change the world. One heart at a time. The intense gaze of an engaged reader.

Each day I am a researcher in the field. Observing. Listening. Note taking. Talking with my subjects. Don't ignore all the little signs that readers are fully engaged. Hunched over in anticipation. Hand underneath the next page ready to turn. A gasp. A sigh. An UGH. And my favorite: "Mrs. Riedmiller!!!!! ..........." How did we get here? Well, it took a lot of hard work. It took a teacher who chooses to read a lot because she finally loves it again, it took daily protected time for reading, it took support for readers while they stretched out their limbs, it took a library full of engaging books that just happen to be there for these particular readers, it took a library down the hall and down in the valley to fill my gaps, it took readers seeing their teacher as a reader too. It also took their teacher deciding the only materials they needed were books and notebooks. It took their teacher dropping all of the TPT bullshit. It took their teacher pulling a Mr. Acevedo and saying "this is a no worksheet zone!" It is hard work. However, it is work that can and must be done. How can we encourage other teachers in our building to join this journey with us? It isn't enough that we are the only ones (or one of few) doing this work. You have the community in your own classroom? Guess what? Now it's your sole mission to bring it to every other classroom in your building. In your district. Don't like how heavy it feels? Then you need to walk away from this post right now. Come back when you're ready. Somehow, we need to take a step back. Take a step back from all the interventions, all of the material purchasing, all of the red tape, and decide that we value literacy. We value it in a way that says we will fight to get books into kids hands, and those books will be ones the readers picked, not us. We value it in a way that means we will continue to grow as educators, even when the district mandated PD might not be what does it for us. My core support group is filled with people that don't even live in my state. Reach out. We're out here, I promise. We value it in a way that shows it because we make time for it. You make time for the things you value. Period. If you value a packet full of graphic organizers over a book a kid chose in his own hands, then shame on you. It's not good enough that you say "this is how we've always done it." It's not good enough that you feel like your hands are tied. It's not good enough to continue to say that no one listens to your requests. Get louder! Get smarter! Get tougher! This fight is ours. It's on our shoulders, it's our responsibility. We can't continue to blame administration or whoever else is in the way that week. Stop telling your kids to have a growth mindset when you don't. Stop throwing RIGOR in their face when you shut down at the mere assumption that the answer is no. The top paragraph showcases what I want, and I am not willing to give it up. If you want it too, you have to fight for it. Ask the tough questions, push back when decisions are made that don't contribute to the greater good. Fight for what you believe in! Get up. Dust yourself off and get back to work. We are here to serve kids. No one else. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed